Today we are publishing the third and last part of the Interview that the CM Communication Office has had with the film director Cam Cowen, on the occasion of his making of the film “OPEKA”; about our confrere, Pedro Opeka, CM. Besides the fact Cowen is sensitive to the situation of the poor in Madagascar, we can find out, besides how the documentary was made, how the meeting with this missionary has influenced his life.

What has this experience of filming Father Opeka’s ministry brought to you as a director and as a man?

As a director, I knew there would be a potential tension between my wanting to make an honest film and having such great admiration for Father Pedro, and I had to keep reminding myself of my mission. It is difficult to be in his presence and not be enthralled, and it is difficult to bear witness to what he has accomplished and not be in awe. I tried not to glorify him and his work and to capture him as a full human being. I hope I have accomplished that. I suspect there are moments in the film that Father Pedro doesn’t like or wishes were not included, and if so, then I probably succeeded. In this process, because I was tested, I believe I became even more committed to honest story telling through film.

As a director, I knew there would be a potential tension between my wanting to make an honest film and having such great admiration for Father Pedro, and I had to keep reminding myself of my mission. It is difficult to be in his presence and not be enthralled, and it is difficult to bear witness to what he has accomplished and not be in awe. I tried not to glorify him and his work and to capture him as a full human being. I hope I have accomplished that. I suspect there are moments in the film that Father Pedro doesn’t like or wishes were not included, and if so, then I probably succeeded. In this process, because I was tested, I believe I became even more committed to honest story telling through film.

As a man, well, that is personally more difficult to express. Like Father Pedro, I resist revealing private feelings, but I’ll give it a try. I can say that I am not a religiously devout person. I was focused on Father Pedro as a humanitarian, not as a Catholic missionary. He once asked me at lunch if I prayed, and I told him I did not. He then conjectured that I probably prayed in my own way. I think I responded with something inane about spirituality. I will say this: being in his presence and feeling his passion for justice, witnessing how hard he fights for his “brothers and sisters,” hearing about his deep and unwavering faith, and witnessing the collective power created from his epic Masses, I probably came as close to God’s energy as someone like me can.

Can you share with us an anecdote regarding the documentary, something the camera did not show and that you would like to share with the audience from our Congregation?

In late 2015, Father Pedro came to the U.S. to receive the Spirit of Service Award from St. John’s University. My wife and I attended the awards dinner, and a couple of days later I visited Father Pedro while he was staying on the St. John’s campus. We went on a tour of the campus, and when we got to the varsity soccer field, he was asked by one of the guides, knowing Father Pedro’s background, if he would like to kick a few goals.

The field was made of artificial turf, and that appeared to be the first time he had been on that surface. He took off his shoes and started to do some warmup exercises while the guide went to fetch a soccer ball. When he returned, Father Pedro said to me, “Cam, you go in the goal.” He and I had already developed a competitive banter, so of course I said I would. I had played soccer in my youth and felt I could keep him from scoring.

He placed the ball on the outside of the penalty box – 18 yards from the goal. He looked up at me and said, “Cam, I am sorry. I am sorry.” He then began to fire the ball at me with his feet. Either  foot, left or right, the balls kept coming at me at intense speeds. And students in the area began to gather around and watch, because they heard the crack of his stocking feet hitting the ball and saw a man in a gray suit with a mane of white hair and a big white beard doing the kicking. I was able to keep most of the balls out of the goal, but my ungloved hands were on fire from the power of his kicks.

foot, left or right, the balls kept coming at me at intense speeds. And students in the area began to gather around and watch, because they heard the crack of his stocking feet hitting the ball and saw a man in a gray suit with a mane of white hair and a big white beard doing the kicking. I was able to keep most of the balls out of the goal, but my ungloved hands were on fire from the power of his kicks.

He then took a short break, put the ball back on the outside of the penalty box. He again said, “Cam, I am sorry. I am sorry.” He then started to loft the balls in a perfect arc over my outstretched hands and into the goal, almost every time and to the applause of the crowd.

In late 2019, I wanted to capture him on film kicking goals at Akamasoa. So, I challenged him to a repeat of that day at St. John’s. The result was about the same, except this time, even with goalkeeper gloves on, I came away with a damaged left finger that took weeks to heal.

I like this personal anecdote because it reveals Father Pedro as highly competitive, still very athletic, and always fun-loving and playful, traits which might escape notice in the film.

In our film, Father Pedro makes reference to the St. John’s field. I won’t spoil the scene by saying more. Also, in the trailer and the film, we have clips of Father Pedro kicking goals that day in 2019 in his Argentina football jersey.

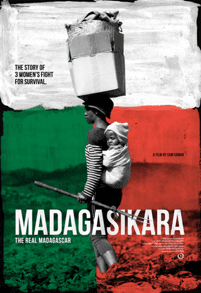

We are thinking about your previous documentary MADAGASIKARA, now. In that production, you paid special attention to the rights of the marginalized, to the struggle to claim these rights and above all to the hope. How are you dealing with these issues in OPEKA?

In “MADAGASIKARA”, we follow the lives of three strong Malagasy women and their families, as representatives of 90% of the population of the country struggling to survive. It is an uncomfortable film to watch for many, because we were trying to present the “real” Madagascar and not an artificially constructed story with a third-act happy resolution. A recent review of the film commented that, “The film is decidedly free of crafted exposition or images designed to spur some exploitive emotion. This is the reality, a stark, unfiltered observation that shows a people who find and define in the darkest times what it means to be human when so much

In “MADAGASIKARA”, we follow the lives of three strong Malagasy women and their families, as representatives of 90% of the population of the country struggling to survive. It is an uncomfortable film to watch for many, because we were trying to present the “real” Madagascar and not an artificially constructed story with a third-act happy resolution. A recent review of the film commented that, “The film is decidedly free of crafted exposition or images designed to spur some exploitive emotion. This is the reality, a stark, unfiltered observation that shows a people who find and define in the darkest times what it means to be human when so much  of what most take for granted is stripped away.” (David Duprey, That Moment In, May 24, 2020)

of what most take for granted is stripped away.” (David Duprey, That Moment In, May 24, 2020)

Their perseverance, resilience and dedication to their children in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles is the hope conveyed in the film: “These are not helpless women, not unintelligent, and not seeking pity. They have carved out what would seem impossible fortitude in a time and place where futility seems borne from every moment.”

In “OPEKA”, there is a critique about the government’s failure to address the extreme poverty in the country and to provide the population with adequate food, water, shelter, health and education. But most of the film is about action – concrete action – taken by a man to restore those rights where the government has failed.

At a social level, we want this story to convey that extreme poverty is not inevitable. We want our audience to see that out of the worst possible conditions – a deadly landfill site – a shining city on the hill can rise up and provide hope and dignity and become the source of educated and empowered children who might one day save their own country.

At an individual level, we want this story to inspire each of us – anywhere in the world – to try to be better. Pedro Opeka’s example is powerful. His life’s theme, in his words that “justice must be the basis of all our actions,” is instructive and illuminating. But it is the power of his will to do justice that we hope we have conveyed. The power of his will can inspire us all.