Its fame is unfortunately not the most glorious. We know this: the city is the starting point of the Coronavirus pandemic which has swept our planet since December 2019. This disaster has caused many miseries which have destabilized our society.

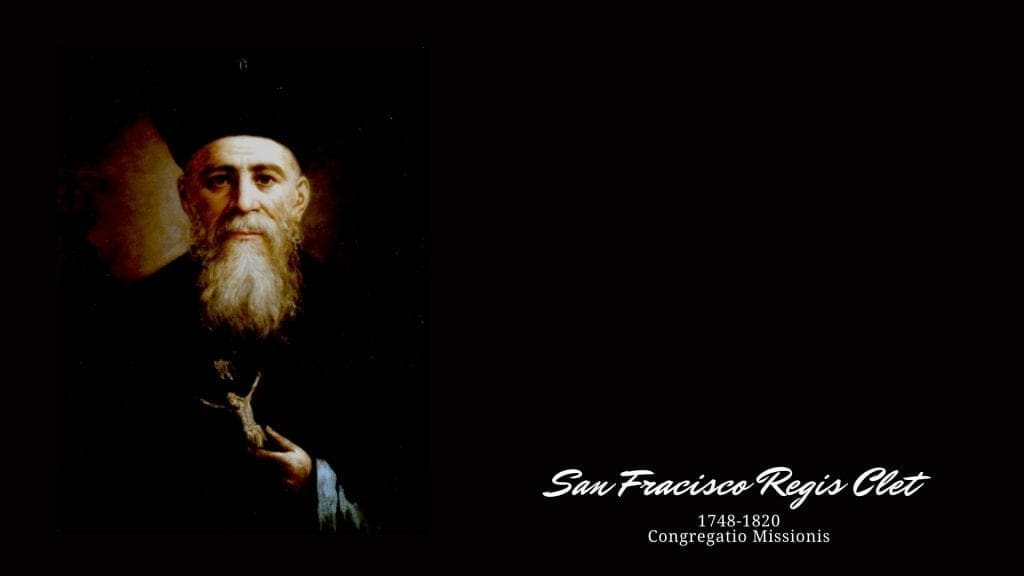

However, Wuhan is not unknown to Christianity. Indeed, we venerate the memory of two Vincentian confreres who were martyred there in the nineteenth century, Saint Francis Regis Clet in 1820 and Saint John Gabriel Perboyre in 1840.

In the year 2020, we are celebrating the second centenary of the death of Saint Francis Regis Clet as well as the twentieth anniversary of his canonization. Indeed, John Paul II, to remind you that the Catholic faith has been alive for a long time in China, decided to canonize 120 martyrs from China, on October 1, 2000 on the feast of Saint Theresa of Lisieux, patron of missions.

In the year 2020, we are celebrating the second centenary of the death of Saint Francis Regis Clet as well as the twentieth anniversary of his canonization. Indeed, John Paul II, to remind you that the Catholic faith has been alive for a long time in China, decided to canonize 120 martyrs from China, on October 1, 2000 on the feast of Saint Theresa of Lisieux, patron of missions.

Francis Regis Clet was born in Grenoble, France, on August 19, 1748. Tenth of a family of fifteen children, he received the name of Francis Regis in honor of Saint Francis Regis (1597-1640), Jesuit apostle of the Velay and Vivarais districts in France. At age twenty, he entered the internal seminary in Lyons. Ordained a priest on March 27, 1773, he wanted to celebrate one of his first masses at Notre-Dame de Valfleury, not far from Saint Etienne. This pilgrimage center, entrusted to the Vincentians since 1687, is well known to us since Father Nicolle founded the Confraternity of the Holy Agony in 1862.

He was then sent as a professor of moral theology to the major seminary of Annecy, whose foundation dates to the time of Saint Vincent de Paul. During the fifteen years he spent there, he was noted for his high virtue, his work, and the depth of his teaching, which earned him the affectionate nickname “living library.”

At that time, France was experiencing a period of internal peace. The accession in 1774 of Louis XVI to the throne of France aroused much sympathy and hope. However, he lacked the courage to undertake expected reforms. The riots that took place here and there were the prelude to the events that would bring about the French Revolution. The Church itself was no exception to this protest movement which disturbed all the strata of society. This is a reason why Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Society of Jesus in 1773. After this, the Vincentians, with much hesitation, were called to replace the Jesuits in the Near East and in China.

Francis Regis, despite this pre-revolutionary atmosphere, agreed in 1788 to be appointed as director of the internal seminary or novitiate of the Priests of the Mission. He then lived at the house of Saint Lazare, north of Paris. Since the time of Saint Vincent de Paul, it had been the Mother House of the Congregation of the Mission, which has earned its occupants the name of Lazarists.

Francis Regis would not have time to give himself entirely to his new role. A year later, on July 13, 1789, a compact crowd of rioters sacked Saint Lazare while waiting to deliver themselves on the following day to the bloody capture of the Bastille, the starting point of the French Revolution. The Fathers were more or less distraught and everyone was looking for the best way to fulfill his vocation. Suddenly, our future martyr expressed his desire to devote himself to the mission of China. Just before he left, he wrote to his older sister, “Do not try to distract me from this trip, because I have made up my mind. Far from turning away from it, you must congratulate me on the fact that God is granting me the noteworthy fervor of laboring in his work.” On April 2, 1791, he embarked in Lorient to arrive, six months later, in Macao, a Portuguese possession in the south-east of China.

Shortly after, he was appointed to go to Kiang-si (or Jiangxi). Disguised as a Chinese, wearing behind his head an artificial pigtail, he adapted to the requirements of his new life, as he explained: “We do not know this soft thickness of mattress; rather, a board on which is spread a light layer of straw, covered with a mat and a carpet, then a more or less warm blanket in which we wrap ourselves, this is our bed. ”

After a year, his superior asked him to go to the neighboring province of Houkouang (Hupeh/Hubei and Hunan), where he would stay for twenty-seven years. As soon as he arrived, the two colleagues present died one in prison and the other from illness. For several years Francis Regis would remain alone to meet the needs of ten thousand Christians spread over an immense territory where he sometimes had to travel more than 600 km. He gave himself totally to his mission to the point that his superior in Beijing asked him to “put limits on his zeal.”

There were many difficulties. The Christians, in general, were economically and educationally. They had to face periods of famine, and some found it difficult to accept all the requirements of the Christian life. Insecurity was permanent because of the brigands, certain rebel groups in the central power, and especially the distrust toward the Christian religion perceived as a doctrine opposed to Chinese culture.

The state of persecution was latent but would develop from 1811. Francis Regis had to exercise caution. In 1818, he led a life of a hunted person with a price on his head. Despite this, on June 16, 1819, soldiers, after denunciation by a Christian apostate, brutally arrested him. The mandarin who judged him wanted him to confess the names of the Christians or missionaries that he knew. For this, kneeling for several hours on iron chains with his hands tied behind his back, he received multiple blows given with a thick leather sole, to the point that his face became all bloody. He was then dragged from prison to prison, and was transferred to the capital of Houkouang province, in Ou-tchang-fou, today’s Wuhan. Locked in a wooden cage, with irons on his feet, handcuffed, and with chains on his neck, he had to endure a journey of twenty days.

He then knew what was awaiting him. The emperor’s decision wasted no time in coming: he was condemned to death “for having corrupted many people by his false religion.” On February 18, 1820, Francis Regis Clet was tortured. In front of the cross where he was to be tied, he knelt in the snow for a final prayer, then said peacefully: “tie me.” With quiet gravity, he underwent without a cry the triple strangulation in use in China for foreigners.

The Christians were able to recover the precious relics of the martyr. This is how his bloodstained tunic was presented to the seminarians of Paris by Saint John Gabriel Perboyre who declared: “What happiness for us if one day we would have the same fate!” It would not be long. Having joined the Chinese mission, he was martyred under the same conditions and in the same place twenty years later.

The remains of Saint Francis Regis Clet and Saint John Gabriel Perboyre now rest in the Saint Vincent de Paul chapel in Paris. The feast of Saint Francis Regis Clet is celebrated on July 9.

YVES DANJOU