I grew up in a far away place in the interior of Paraguay, where only when I was about 10 years old did electricity arrive. Therefore, it was normal for me to be around my house at night, there was a lot of darkness, except when there was a full moon. I think that’s why I was never afraid of the darkness, and it was hard for me to understand the people whom I met later, who were very afraid of darkness.

I remember an incident with a friend of mine who was born and raised in the city. He was not able to stay in a dark place. Once I invited him to stay in a dark, open field, and he said he would accept as long as I didn’t make a joke about running away and leaving him alone. The pact made, we plunged into a place devoid of all light. At first, I could hear that his breathing was agitated, but after a few moments when I pointed out some of the stars, in a few minutes, he began to enjoy the moment and the place. And the darkness became peaceful for him.

From this singular experience with my friend, I would like to bring to mind here what happened with another friend (this one, a very special one, through time): Louise de Marillac. She went through one of the darkest nights a person could experience. She went into depression, she doubted God… she surely felt alone and was in darkness. However, in order to appreciate the richness of her life experience, this precise moment of the light of Pentecost is crucial. To take up what was said in the previous paragraph, perhaps Saint Louise was full of fear in the face of that darkness, but suddenly she was no longer lonely and she was able to find light there.

To try to understand the richness and depth of “the light of Pentecost” in Saint Louise, we will look at the dates, the characters, the personal context and the vocation that can be glimpsed there.

Dates

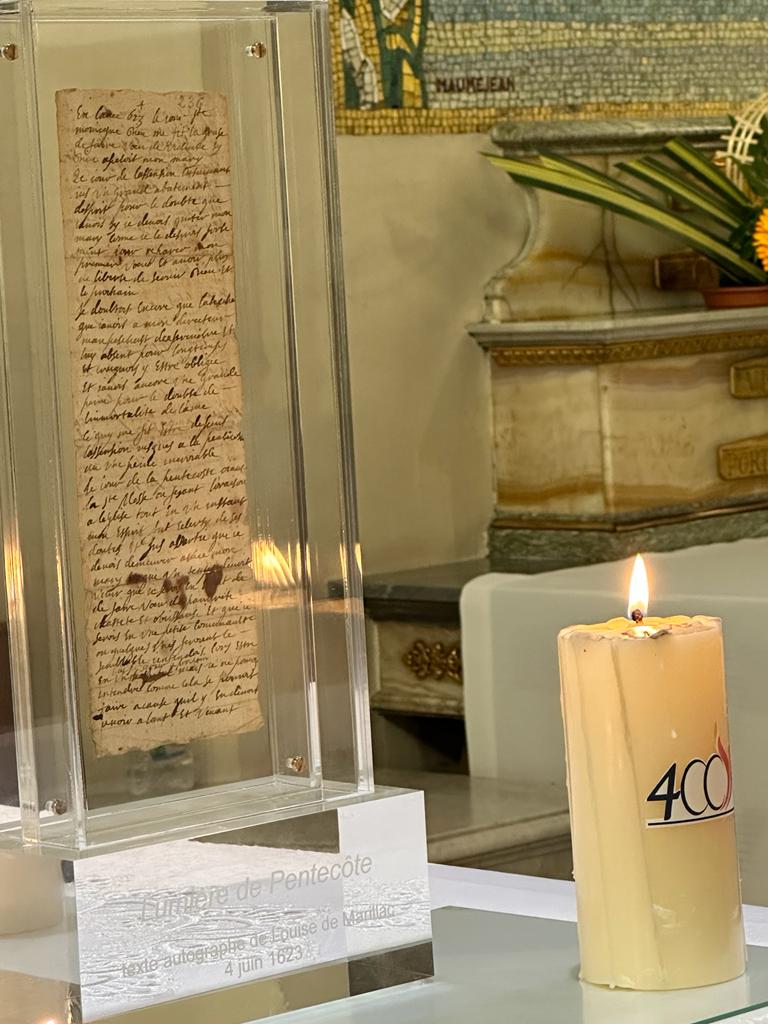

Experience, in general, implies an event that can be dated. However, in a mystical experience, not everything can be dated, let alone empirically verified, but the effects that are triggered by the episode act as a motivator to give feedback on the importance of what happened. 1623 is a key year in St Louise’s chronology: it is the year of darkness, but also of light. In her account of this experience she mentions two dates (St. Monica’s Day and the Ascension of the Lord) that lead to “the light”, which will take place on 4 June 1623:

“In the year 1623, on the feast of St. Monica[1] , God granted me the grace to make a vow of widowhood if God would take my husband. The following Ascension Day[2] , I fell into a great dejection of spirit, because of the doubt I had as to whether I should leave my husband, as I insistently desired, in order to repair my first vow and have more freedom to serve God and the neighbour.” [3]

Characters

Our personal and Christian life is a journey with others. The God of our faith is a God-Trinity-Community. From this reality we can understand that St. Louise walked with others, although often groping, in their process of human and spiritual maturation. As I mentioned in the introduction, perhaps in the face of this great crisis she felt alone because the darkness was so great, yet objectively she is the woman who always looked for companions on the way.

In the “light of Pentecost” there are implicitly two people who helped her at the time of “the passage from darkness to light” (cf. 1Pt 2,9) and who were still on pilgrimage on earth: John Peter Camus and Vincent de Paul. The first being her spiritual director, to whom she was so attached, but as he has been appointed Bishop of Belley, she will soon have to take another one. Here appears the second, who would be St. Vincent:

“I was also assured that I should remain at peace as to my director, and that God would give me another, which he then made me see, as it seems to me, and I felt repugnance in accepting; nevertheless, I consented, feeling that it was not yet when this change should be made.” [4]

In the text of “the light” there also appears one who is already part of the Church in Heaven: St. Francis de Sales. We can see in this the profound experience that St. Louise would have of the communion of saints:

“I have always believed that I received this grace from the Blessed Monsignor of Geneva, because I wished very much, before his death, to communicate this affliction to him, and because afterwards I felt great devotion and received many favours through him, and at that time I know that I had some reason to believe so, which I do not remember now.” [5]

Saint Louise walks with others and with them she rehearses the “step” of God in her life. She is able to see that “the incarnate God” has adopted the human steps to teach her the divine step from the sacred breath that dwells in her: the Holy Spirit. The God-incarnate, who lived his Passover-step to fill with hope the painful steps of men and to remind us that “love is stronger than death”[6] , makes his way with and in Saint Louise.

Personal context

Personal context

At the moment of experiencing “this light” the event that unleashes Louise’s human and spiritual crisis is the illness of Antoine Le Gras, her husband. He had fallen ill in 1621, his mood changed, Louise blamed herself and concluded that because she had not been faithful to “her first vow”, to be a nun, God was punishing her. In this depressed situation, she was once again the woman on pilgrimage with others, especially her uncle Michael de Marillac and Bishop de Camus. Faced with her personal context, she sought answers. Perhaps she asks herself “why”. The answer to “why” is not always easy to find. Probably his companions on the road will have helped him to change this questioning into a “why”. Thus, from the concrete fact, he is able to open up to “the light”. The personal-human experience needs to open up to transcendence, otherwise it remains in a painful emptiness and a deafening silence; she was able to take the step, led by the Holy Spirit.

Vocation

In the midst of the darkness of her crisis, she receives an important light on her vocation. In the text, the mission to which God calls her is expressed. The text reads:

“There would come a time when I would be in a position to take a vow of poverty, chastity and obedience, and that I would be in a small community in which some would do the same. I understood that this would be in a place dedicated to serving my neighbour; but I could not understand how it could be, because there would be a movement of comings and goings.[7]

We can underline that in that experience, which was later expressed in writing, St. Louise’s vocational path is illuminated: To what is she called? To serve Him in her neighbour. Where? In a place dedicated to service. With whom? With others who would do the same. And she concludes this vocational illumination with something that she says she cannot understand “because there must have been movements of comings and goings”, however, this which was not clear at the beginning, when “God’s dream” crystallised in the Company of the Daughters of Charity, will be the characteristic that dresses with novelty the new style of lay life for the service of neighbour, which St. Vincent de Paul in turn will emphasise saying: “I was called to serve God in the service of neighbour”:

“Having no other monastery than the houses of the sick, and that in which the superior resides, no other cell than a rented room, no other chapel than the parish church, no other cloister than the streets of the city, no other enclosure than obedience, having to go only to the house of the sick or to the places necessary for their service, no other bars than the fear of God, no other veil than holy modesty, and as they have made no other profession to secure their vocation than the continuous trust in divine Providence;And as they have made no other profession to secure their vocation than a continual trust in Divine Providence”. [8]

These words of St Vincent breathe freedom, which is none other than that which flows from the Spirit and fully disposes us to serve with greater self-giving love.

Conclusion:

God is the one who gave Saint Louise this experience, he is the light and at the same time the source of the light that comes to her. St. Louise is the recipient of the light-grace. The words of her writings express this reality: “I was enlightened, I was warned, I was assured, it was taken from me”. The divine “Other” is remaking St. Louise. Like the people of Israel, she experiences an exodus, and therefore also a liberation. This God, who creates (cf. Gen 1 and 2) and who liberates (cf. Ex 15), recreates her, so that she is at peace and prepared for her mission.

With a confrere, a priest of the Congregation – he is a scholar of our charism – we often talk about a great challenge we have as a family: to discover in our saints the process of fortitude with which they faced the “dark nights” and to learn from them. When a brother, a sister, a lay person of our Vincentian family is in crisis, we turn to “other wells” to quench that thirst, and we forget to explore in our Vincentian tradition, witnessed in the experience of the founders, saints and blesseds, how they managed their “dark nights” and how they let God illuminate those stretches of the road.

In this year in which we celebrate the 400th anniversary of the “light” of Pentecost in Saint Louise, may we learn from her this openness to the Holy Spirit, so that with her intercession, we may also make a little path of light that helps to illuminate the steps of other light seekers, like us, beyond our darkness. So that we may live the reality presented to us in the first letter of Peter:

“You are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people chosen to proclaim the wonderful deeds of him who called you out of darkness into his marvellous light”. (1Pt 2,9)

Hugo R. Sosa, CM

[1] According to the liturgical calendar of that time, it was Thursday, May 4, 1623.

[2] It was Thursday 25 May 1623.

[3] SAINT LUISA DE MARILLAC. Correspondencia y escritos. Salamanca: CEME, 1985, 11 (Hereafter SLM).

[4] Ibid. 11

[5] Ibid. 11

[6] Cf. Benedict XVI – Homily at the Easter Vigil 2007.

[7] SLM, 11.

[8] SAINT VINCENT DE PAUL. Obras Completas. Salamanca: Sígueme-CEME, 1972-1986, IX/2, 1178-79.

I have always had a devotion to St Louise because of how she was able to transcend the complexities of her life. From the painful circumstances of her origins, the stigma that enveloped her because of this, the indifference her own family showed; and on to the coldness of St Vincent during the last days of her life. I could relate to her struggles and she was one I could depend upon to help me accept God’s will, where true peace

is found